Before we read the words of Genesis 11.1 we should note that in Genesis 10 there have been references to the scattering of Noah's sons and the different peoples and languages they speak. So when we come to chapter 11 we should notice that we have a different story, probably from a different source. It's here not because it is what we would think of as a historical account, but because the legend has things to teach us in God's providence. I don't think that the people who put this all together were ignorant of the 'contradictions', probably being more oral than literary, they were even more cognisant of them than we skim-readers tend to be, but they understood them to be conveying different truths than merely historical fact.

Genesis 11.1 Now the whole earth had one language and the same words....4 Then they said, "Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth."... 6 And the Lord said, "Look, they are one people, and they have all one language; and this is only the beginning of what they will do; nothing that they propose to do will now be impossible for them. 7 Come, let us go down, and confuse their language there, so that they will not understand one another's speech." 8 So the Lord scattered them abroad from there over the face of all the earth, and they left off building the city.

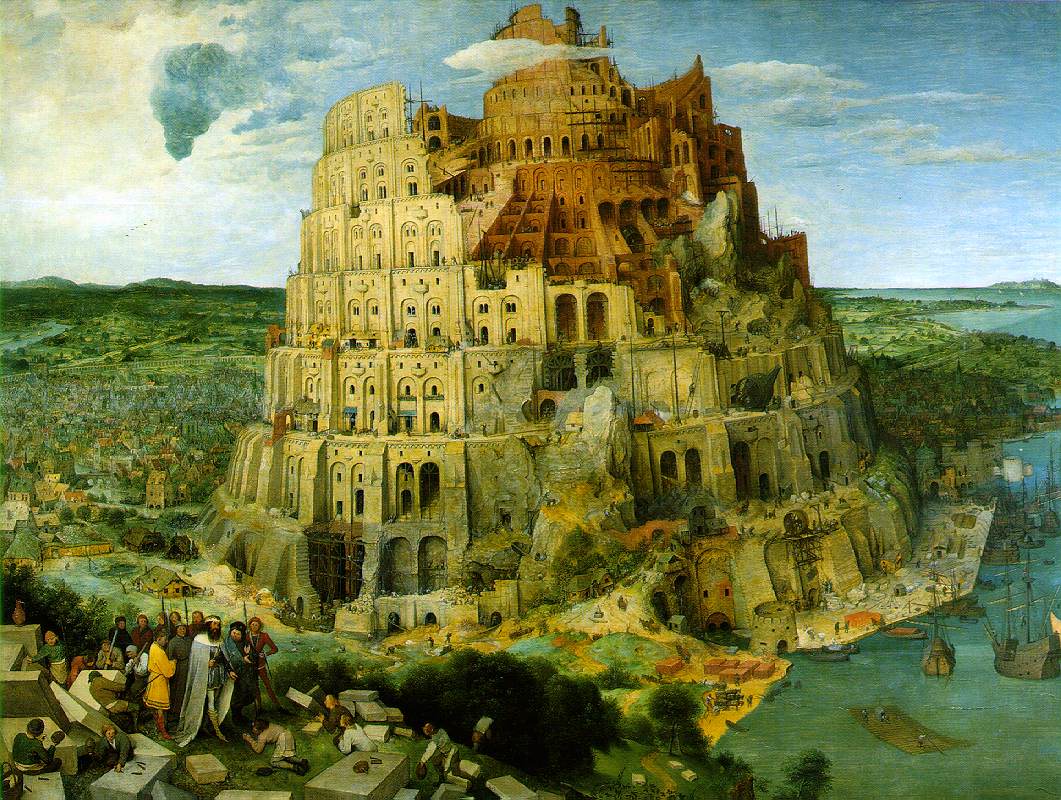

What really strikes me here is the connection between speaking the same language and forming a society whose potential for succeeding in large projects is huge. We are not really told why this is a bad thing. In the context of human sinfulness apparently growing through Genesis, probably the risk is that collaboration in evil in the form of oppression and violence is not far behind. Certainly the biggest hint about the 'problem' lies in the three things mentioned in verse 4: the pride of touching God's realm, the heavens [as it would have been seen then, at least metaphorically], the desire to exalt their own society 'making a name for themselves' which smacks of idolatry in embryo, and the desire not to be scattered suggesting a recognition of strength in unity and numbers. It is a kind of grudging acknowledgement of the power of that supreme human artefact, 'the city'. However, there lies danger in it being undertaken as a kind of rivalry to God's enterprise. Their unity is potentially God-exclusive and injustice-friendly.

For the linguist, the interest of all this lies in seeing the role of language in unifying and establishing both a sense of social identity and a means of organising collaboration. The sense of identity given by language is studied today in sociolinguistics where the way that we speak is related to feelings of solidarity and self-situation or prejudice in relation to power.

Collaboration is harder when language differs, not only because it is harder to communicate, but because the entailments are of different ways to think about things culturally to, to value things differently and to make differing basic assumptions.

I find it interesting, too, how there seems to be a parallelism between confusing language and scattering, as if the two are mutually interrelated. In fact, that is how it tends to work, distance, whether social, cultural, geographical or political, tends to open up linguistic changes and reinforce them and, in turn, linguistic differences tend to exacerbate other social differences. An interesting thing is how quickly language can change, especially if not written. Written languages seem to change less quickly. We have fragmentary records of some Celtic [gaulish] sentences from the Roman era, and it is very different, grammatically, from what emerges only a few hundred years later, after the collapse of the Empire. The social upheaval seems to have meant very rapid change.

If it is right that this is here as a warning, it does seem to me to have a political lesson: that decentralisation is a good thing in that it helps to mitigate the evil that human collaboration is capable of [perhaps our most recent chilling symbols are Ausczhwitz and Fat Boy]. Language is both the sign and driver of unity and disunity; it can play a role in drawing people together and driving them apart. Which is why the day of Pentecost is often read against the background of the Babel story: they are two thematic poles of scattering and unifying with or without God.

To me this story legitimises the linguistic, particularly the sociolinguistic enterprise. Understanding human difference and similarity in relation to language is perhaps the clearest indicator or index of what is happening. Understanding human similarity and difference as each having positive and negative aspects and not simply seeing unity as an unproblematic good [try fascism!] or diversity as solely as an ill to be overcome.

Crosswalk.com - Genesis 11:

Last posting in this series ...

No comments:

Post a Comment