Most of us never notice the mildly complex 'dance' we do when sharing the pavement with people walking the other way. It starts about 30 yards away on a clear causeway, closer obviously if the line of sight is obscured by people or objects. We look at the person coming our way and make a judgement about what trajectory they're taking. If it looks like it may intersect with our own, we each make little course adjustments all the while checking out the other's adjustments and if necessary adjusting further. Normally this allows both parties to devise non-intersecting routes in fairly short order. Just occasionally the random re-selecting of trajectories results not in a non-intersect but in a repeated intersect and we do that dance of apologetic sidestepping until we may even have to verbally or gesturally unjam our little quasi-crash. Most of the time we don't even consciously notice we're doing all of that.

BUT ... when someone is not looking because their gaze is entangled in a screen as they walk, all of that reading the tiny adjustments to trajectory is thrown awry, even worse when they are given occasional attention to the walkway because then you don't know for sure what they may have seen or not seen, whether they are going to continue or check -and certainly you can't assume that they will notice that because, for instance, you have people either side of you, you have little room for manoeuvre. Head in a smart-phone? Grrr: non-cooperative pedestrian.

I used to do it until I realised that it made me a pain to anticipate and increased my chances of collision or near-collision. I now tend to stop and find a spot out of the way of the main flow of walkers to deal with my text message or map directions. Please, people, do likewise and stop getting in the way of the rest of us who are paying attention to what we're doing. ...

L'enfer, c'est vraiement les autres. Nous vous remercions de la phrase, M. Sartre.

Nous like scouse or French -oui? We wee whee all the way ... to mind us a bunch of thunks. Too much information? How could that be?

28 June 2012

25 June 2012

Tax, reward and the favours of fortune

I'm feeling a bit vindicated reading the report of this research. I've been saying in several posts over the last couple of years that we should be aware that the talk of rewarding the entrepreneurial is overblown by giving too much credit to their 'exceptional' ability (ie it's not normally that exceptional) and too little to circumstances and the formation by their society (if it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a nation to raise an entrepreneur). This study shows that we humans have a confirmation bias about this that needs challenging. Hey, -and it has a pedagogic dimension too!

"Humans, however, often rely on the heuristic of learning from the most successful. Our research found that even though observers were given clear feedback and incentives to be accurate in their judgement of performers, 58% of them still assumed the most successful were the most skilled when they are clearly not, mistaking luck for skill. This assumption is likely lead to disappointment -- even if you can imitate everything Bill Gates did, you will not be able to replicate his initial fortune. This also implies that rewarding the highest performers can be detrimental or even dangerous because imitators are unlikely to achieve exceptional performance without luck unless they take excessive risk or cheat, which may partly explain the recurrent financial crises and scandals." Reward the second best, ignore the best:And because their success often is magnified or amplified by those good old dynamics to do with the first player in the field being able to set the parameters, make faster progress, accumulate critical economies of scale etc, we should consider a kind of windfall tax approach. I'ts like in the game Monopoly, the ones who get to the premium properties first and have a half decent strategy tend to win; it's not skill, it's luck plus, as I say, a half-decent strategy (but probably no better than most of the other players).

The lucky few may be more skilful than others eventually, but the way they gain their superior skill can be due to strong rich-get-richer dynamics combined with the good fortune of being successful initially. This can justify a higher tax rate for the richest when their extreme fortune is accumulated in the fortunate fashion defined in this research.And I thought it quite interesting to note that we need to try to work against the apparently counter-intuitivity about rewards in this kind of case:

policy-makers need to design 'nudges' to help people resist the temptation to reward or imitate the top performers.Part of what needs to happen though, surely, is that we keep banging on about this research and we keep analysing and publishing and highlighting the luck and happenstance that has actually 'made' these so-called 'self-made men'. Society has helped make them; the rest of us are entitled to ask for a dividend for the investment we have made in their success. We are all shareholders in the common good; it's time to stop exempting those who impress us.

24 June 2012

Mutiny continues

Increasingly there is a link to the current post -banking-crash, post-'Occupy', mid-austerity world. The way-in to that is noting that the monopolistic tendency historically tends towards blockage and stifling of creativity. One craven example of this is the copyright regime and it becomes particularly pointed in relation to performed music. Kester homes in on Mick Jagger because (perhaps ironically given his rock'n'roll image) he supports the extension of copyright on music. Apparently Jagger wants money to roll in for his family from his record sales for a long time. And yet, we are reminded, how much of Jagger's oeuvre is totally new? -Like much creativity the cleverness is about remix and development. And indeed, Jagger has benefitted from being a performer in a unique window of history when recording was possible but not easily 'ripped'. It's hard to be sympathetic for the guy (who has clearly sold out and has become the man).

"People are naturally going to feel less inclined to listen to Mick Jagger's concerns about being paid for years and years more for songs he wrote and made millions from years and years ago. What much of the recent mood of protest has been about is the lack of a perceived principle of fairness ... how long did it take for Mick Jagger to write 'Street Fighting man'? Perhaps 20 hours. And on a generous wage of .... time for recording ... equipment ... marketting ... $15000. Many of the Stones singles sold well over 500,000 copies. At what point would it be fair to say that Mick Jagger has received a fair reward for his labour?"

My comment: It is obviously a question that could be asked of many others: they happen to to found themselves occupying an gilded position in the economy and have enough talent to exploit it. We should stop buying the myth that they are uniquely talented individuals entirely worth it from their own exclusive and unaided resources. I've been around enough to know that there are actually hundreds of people, probably thousands, that in every respect that enabled Jagger and his ilk to exploit the gilded position they found themselves in would be just as capable of producing 'good stuff' in terms of writing, performance and business acumen. This gilded position is borne of things like being in the right place at the right time and to have received an education developing their abilities and to have been socialised in a way to be able to connect with monetisable trends.

So it is that copyright, overextended, allows commons to be enclosed. It's fair enough to be able to make back some reward for the effort and work put in; but not in a way that fails to recognise the indebtedness of the author/maker to wider society or the possibility that others might build upon the work. If that doesn't happen, the injustice of it makes for conditions which are likely to produce 'piracy'.

"People are naturally going to feel less inclined to listen to Mick Jagger's concerns about being paid for years and years more for songs he wrote and made millions from years and years ago. What much of the recent mood of protest has been about is the lack of a perceived principle of fairness ... how long did it take for Mick Jagger to write 'Street Fighting man'? Perhaps 20 hours. And on a generous wage of .... time for recording ... equipment ... marketting ... $15000. Many of the Stones singles sold well over 500,000 copies. At what point would it be fair to say that Mick Jagger has received a fair reward for his labour?"

My comment: It is obviously a question that could be asked of many others: they happen to to found themselves occupying an gilded position in the economy and have enough talent to exploit it. We should stop buying the myth that they are uniquely talented individuals entirely worth it from their own exclusive and unaided resources. I've been around enough to know that there are actually hundreds of people, probably thousands, that in every respect that enabled Jagger and his ilk to exploit the gilded position they found themselves in would be just as capable of producing 'good stuff' in terms of writing, performance and business acumen. This gilded position is borne of things like being in the right place at the right time and to have received an education developing their abilities and to have been socialised in a way to be able to connect with monetisable trends.

So it is that copyright, overextended, allows commons to be enclosed. It's fair enough to be able to make back some reward for the effort and work put in; but not in a way that fails to recognise the indebtedness of the author/maker to wider society or the possibility that others might build upon the work. If that doesn't happen, the injustice of it makes for conditions which are likely to produce 'piracy'.

23 June 2012

Still in Mutiny

The big theme of Mutiny -at least as far as I've read to this point (about a third of the way through) is about the conflict between two views of the world; on one hand there are those who seek to extract maximum economic value from what they own and to own more property from which to extract value even if that means exploiting people and reducing them to machine-like servitude. On the other hand are those who suffer the consequences of those ways of conducting oneself who fight back to preserve, regain or protest their dignity, rights to life and livelihood.

This then influences how we define 'pirate':

"This, then, is what we can take 'pirate' to mean: one who emerges to defend the commons wherever homes, cultures or economies become 'blocked' by the rich. Be it land that is being enclosed, or monopolies that are excluding and censoring, or wealth that has been hoarded, blockages to what should be shared freely and equitably create the conditions in which pirates well be found. Moreover, ... we can conclude that when they rise up, they tend to do so from places of poverty and need, partly because it is the poor and needy who fell the effects of enclosure more immediately ...." (p.50)In effect, we could see the paradigm characterising as commons vs enclosure. It is interesting and helpful to see that paradigmatic dynamic being worked out in more modern kinds of piracy such as radio stations playing music, for example.

Kester's not blind to the criminal potential and makes a distinction between piracy in these 'fighting back' terms and "criminal gangs". And I think he makes a case, in a sense, for seeing some of the state-sponsored enclosure as not much better morally than the action of criminal gangs. In other times and places we sometimes use the term kleptocracy. That said, I would like to see the difference between the TAZ and a criminal gang more fully explored, because, of course, the kleptocratic state tends to paint the former in terms of the latter and thus seeks to neutralise the threat ideologically (largely successfully).

And, of course, we should be reminded that in the 17th and 18th centuries the official religion of the captains and lieutenants who were acting oppressively in the name of the king is the religion that, for the English, the king himself was the temporal head: the Christian religion in the form of the Church of England, or for others Roman Catholicism or Reformed Christianity (Spain, France and the Netherlands were the other main powers involved). It is ironic and I find bitterly sad and angrifying that following Jesus the Christ had been co-opted by state authority and made-over in such a way as to have made enemies of those who really ought to be Jesus's most natural friends by becoming the ideological support for social control of a brutal and egregiously unjust sort. Thus Kester includes the church an the dynamic of the blocked. So retelling the legend of Captain Mission and Fr Caraccioli inspired in me a wistful hope that it might have been true. It turns out to have been written up by Daniel Defoe (available freely here).

More later, I hope ....

Mutiny! -Towards a review

I'm currently reading Kester Brewin's 'Mutiny' and I'm aiming to produce a proper review in due course. But while I read, I thought I'd make a few notes. Maybe in a handful of posts.

One of the things I like about this book, even before I started reading it, is that there is a certain degree of putting his money where his mouth is. In this case, he says;

Kester's aim more generally is about:

So far in reading it, the scene has been set giving a sense of looking most closely at pirates of the 1700's but also other forms of piracy including books and publishing, radio, and looking at modern Somali piracy. Kester points out that he is not seeking to condone violence or robbery, but to understand it (I think that's fair). There have been tales of particular pirates and mention of a pirate utopia. One of the things that I think I've been most interested in is the digging back into particular matters to do with social, political and economic factors.

What in particular I think is worth remembering when considering the piracy in the Caribbean in the 1700's is that the behaviour of the pirates towards other vessels was not noticeably distinctive to that of official naval vessels or privateers: the issue was not robbery or violence used; everyone was doing that. No, the issue was for whom? -Empire or the co-operative venture -for that was often what a pirate vessel was. Many pirates were, it would seem, seeking to escape pressed servitude and arbitrary violence at the hands of their officers. At least on a pirate vessel there might be a degree of democracy, a fairish share of the loot and considerably less risk of violence from ones officers (whom you might have had a hand in voting into office).

Of course, the question is whether Kester's characterising of democracy and fairness was characteristic of pirates as a whole or just the a few of the better ones. But, given, the kinds of conditions they appear to have been attempting to escape, it certainly seems plausible and even likely that it could have been frequent.

The other thing that so far has not been more fully explored, is to ask what the popularity of reading and watching works about pirates is about. Even in the industrial revolution in England the books on pirates were popular. The suggestion is that actually the recognition of a degree of sympathy for protest against brutally maintained monopoly enriching the few by virtually enslaving the many who never get a real sniff of the fruits of their labour...

One of the things I like about this book, even before I started reading it, is that there is a certain degree of putting his money where his mouth is. In this case, he says;

my plan is to make back (some of) an estimated figure of what the book has cost me to write, and then release it into the public domain – probably with an option for a charitable donation. There’s no way a publisher would accept such a limited copyright, so self-publishing was the best way forward.

Kester's aim more generally is about:

controlling the means of production, re-imagining ideas of copyright and being able to say exactly what I want to say. One of the final reasons I’ve wanted to experiment with this concerns the idea of TAZ – the Temporary Autonomous ZoneSo, all in all, a good bunch of reasons to anticipate the book eagerly, and having read a couple of chapters so far, I'm already considering two or three people to buy it for.

So far in reading it, the scene has been set giving a sense of looking most closely at pirates of the 1700's but also other forms of piracy including books and publishing, radio, and looking at modern Somali piracy. Kester points out that he is not seeking to condone violence or robbery, but to understand it (I think that's fair). There have been tales of particular pirates and mention of a pirate utopia. One of the things that I think I've been most interested in is the digging back into particular matters to do with social, political and economic factors.

What in particular I think is worth remembering when considering the piracy in the Caribbean in the 1700's is that the behaviour of the pirates towards other vessels was not noticeably distinctive to that of official naval vessels or privateers: the issue was not robbery or violence used; everyone was doing that. No, the issue was for whom? -Empire or the co-operative venture -for that was often what a pirate vessel was. Many pirates were, it would seem, seeking to escape pressed servitude and arbitrary violence at the hands of their officers. At least on a pirate vessel there might be a degree of democracy, a fairish share of the loot and considerably less risk of violence from ones officers (whom you might have had a hand in voting into office).

Of course, the question is whether Kester's characterising of democracy and fairness was characteristic of pirates as a whole or just the a few of the better ones. But, given, the kinds of conditions they appear to have been attempting to escape, it certainly seems plausible and even likely that it could have been frequent.

The other thing that so far has not been more fully explored, is to ask what the popularity of reading and watching works about pirates is about. Even in the industrial revolution in England the books on pirates were popular. The suggestion is that actually the recognition of a degree of sympathy for protest against brutally maintained monopoly enriching the few by virtually enslaving the many who never get a real sniff of the fruits of their labour...

16 June 2012

C of E, same sex marriage and ethical mismove

I have been uncomfortable to be associated with this: I don't think I agree with the Church of England response to Government same sex marriage consultation -which is a shame because I'm supposed to represent the CofE.

At the heart of the submission is this paragraph:

And this, I think, also outlines the heart of the objection is from an Evangelical perspective. As such it captures my own erstwhile difficulty with affirming homophile relationships from what I used to understand as a biblical perspective. Let me offer a boiled-down version of the what is probably the mainstream Evangelical position as I have experienced it being passed on in England.Such a change would alter the intrinsic nature of marriage as the union of a man and a woman, as enshrined in human institutions throughout history. Marriage benefits society in many ways, not only by promoting mutuality and fidelity, but also by acknowledging an underlying biological complementarity which includes, for many, the possibility of procreation. The law should not seek to define away the underlying, objective, distinctiveness of men and women.

Many British Evangelicals are properly wary of using Levitical law and incidents like Sodom and Gomorrah in discussions about homosexuality. They rightly recognise the cultural differences and hermeneutical difficulties of making a straight transfer from such texts to contemporary life. Such considerations do actually impinge on the thinking (though you'll still find some unreflective 'strategies' of Bible reading which are inconsistent to uses in other areas). The main argument for Evangelicals of this more nuanced ilk is grounded in Jesus' teaching about divorce where he appeals to Genesis 1 and 2 saying that the reason that divorce is not good (and for the moment I don't want to get into divorce per se) is that "at the beginning "made them male and female,'" and that "For this reason ... they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate"

Now, it may not at first sight seem relevant: what has divorce to do with homosexuality? Well, note that the passage links sexual dimorphism with marriage and also with sexual activity ('one flesh' is usually understood as mainly about that -though I am wondering whether that really holds water). That leads to the main argument -popularised by ethicist David Field in 'Homosexuality -a Christian Option?' (the question is answered negatively, but within an argument that discounts many traditional objections like the Sodom one). David Field's argument (from memory) was, effectively, that Jesus is saying that the purpose of sexual activity is to cement a lifelong partnership between one man and one woman. I'm not sure if I've stated that in a critique-proof way but I hope I've captured the main thrust of the argument well enough.

For a long time I was convinced by that argument. At the same time I found I was not homophobic, that is I had no personal difficulty with homosexual people (to the extent that some thought I might be gay myself) and advocated equality for homosexual persons in every other way. I thought of it as being similar to an attitude to adultery or heterosexual unmarried partnerships: I may not condone the activity, but that is no reason to discriminate against people in other areas of life or to take away their rights.

However, I have come to believe that this suppodsedly Biblical approach is fundamentally flawed and cannot sustain the weight being placed upon it. And once it goes, there is no longer any good reason not to accept that homosexual relationship can be analogous to that between a man and a woman. In fact, once that reason has faded away, the arguments for acceptance of gay partnerships gain pre-eminent force. Those arguments were ones that troubled me (when I was persuaded by David Field's position) for a long time and I was aware that the only reason I didn't go with them was that Biblical argument rooted in the reading of Jesus' supposed understanding of Genesis 1 and 2.

However, I have come to believe that this suppodsedly Biblical approach is fundamentally flawed and cannot sustain the weight being placed upon it. And once it goes, there is no longer any good reason not to accept that homosexual relationship can be analogous to that between a man and a woman. In fact, once that reason has faded away, the arguments for acceptance of gay partnerships gain pre-eminent force. Those arguments were ones that troubled me (when I was persuaded by David Field's position) for a long time and I was aware that the only reason I didn't go with them was that Biblical argument rooted in the reading of Jesus' supposed understanding of Genesis 1 and 2.The arguments that disturbed my certainty.

The arguments that disturbed my contentment with David Field's position were things like the following.

One important disturber of my peace was realising that homosexual people don't choose their orientation and consequently that it seems to be an injustice to deny them, point blank, expression of something fairly fundamental to their being in the world, and it certainly seems cruel too.

Then there were the many Christians I found who were good and wholesome growing Christians who were in same-sex partnerships; if God is so concerned, I thought, why would God bless their spiritual lives so without challenging them -yet that challenge really didn't seem to be coming; rather they were blessed and being a blessing. Was God calling us to be less merciful than God?

I also found unconvincing the concomitant idea that if something isn't God's 'norm' or best, we should 'outlaw' it. Contrariwise: there are things that are not the way that we would say that God wants them to be ultimately but which we 'make room for': divorce is perhaps the most germane and obvious, (and some people would add taking up arms in a just war). It seems to me that the logical corollary of this argument is to deny the deaf community the use of sign language because God's norm or best is for them to be hearing. (I say that without intent to be offensive, I trust it is not and apologise if it comes over badly; I think it is affirming of deaf people).

I also found the fact that 'gay cure' therapies seemed not to work on the whole and the times when they apparently did were probably to do with bisexuality, given their paucity. I felt that if the traditional view was right, such therapies ought to have more success.

There is also the intuition that the prohibition of homophile relations should make sense in relation to the law of Love: loving others as God loves and as we love ourselves. If we bracket out, for the moment, promiscuity and other 'unhealthy' ways of living out sexuality (which are on a par with heterosexual morality, btw) and we are dealing with a consensual, equal relationship in which mutual respect, comfort and aid are given and received, then how is that bad? If God is love and those who live in love live in God (1 John 4.16), then this kind of relationship shows forth God. it's hard to see how a sexual dimension to that can be so fundamentally wrong that it erases the goodness of the love. If homosexuality is so fundamentally wrong, then there ought to be intrinsic consequences that quite clearly run against the law of Love: I have not found any. And while that's not a determining argument, it is a consideration that considerably weakens the plausibility of the main position I had held.

Relatedly, it seemed to me that 1 John 4.16 would imply that a loving committed homophile relationship was good and right save only the sexual expression. It then seems quite hard to argue against the sexual expression of such a relationship if it is exclusive and lifelong in intent and unlikely to prove a danger to others.

I also found it intriguing that where an acceptance of the possibility of committed loving homophile relationships reigned, churches seemed to be able to reach out and see people coming to faith from the gay communities. This raised the kind of issue above about God's apparent blessing. More than that, it is hard to escape the parallel with the Church in Acts finding God pushing it to accept gentiles by converting them and giving them the Spirit.

I was also concerned to discover that suicide rates among homosexual people were comparatively high as were other stress-related health outcomes, it seemed to me that the attitudes of stigma that were a large part of the cause of those negative mental health outcomes were being propped up by church attitudes. At the very least, this means that the church has to work a lot harder to affirm gay people to the fullest degree it can in conscience. I fear that this is no way happening and cannot happen without a more fulsome acceptance on an emotional level, and I do suspect homophobia proper (ie people having a strong personal reaction against other people) lies somewhere at the root of that problem.

What's wrong with the creational argument?

So, having dealt with some of the outlying matters, what happened to my reading of that main 'Field' argument? Well, it seems to me now that reading the texts that Jesus refers to in his reply about divorce as a command, in effect, is to over-interpret by making an 'is' into an 'ought'. The 'is' part of it is men and women, being attractive to one another and the possibility of sex and children. That's the way things are: that's an 'is'. The 'ought' comes in at that point: a regulation of these possibilities and the desires that come with them so that they work for the particular and common good (and I won't here go into all of that, suffice to say it's about justice, well-being and love). The problem with the Evangelical view, as per David Field, is that the 'ought' gets moved back onto the male and female aspect so that being male and female becomes a moral imperative rather than simply being recognised as the way that things tend to be normally. This works oppressively when applied to situations where the 'normal' isn't possible: when the 'is' of gender difference becomes an 'ought' -similarly when the 'is' of general child-bearing becomes an 'ought' to the childless or would be if the 'is' of general sexual 'potency' becomes an 'ought' to the injured or ill.

I think that the fact that Jesus was talking about divorce in a context where same-sex relations of any kind are not in view is a big hint that we should be wary of applying it beyond that context in ways that would make unjust and oppressive situations if applied rigorously according to the widened understanding of Field and others. We know that in several parables of Jesus, reading more from it than the main point being addressed is dangerous and misleading. It seems to me that similar caution is warranted here.

Furthermore, I really don't think that anyone reading Jesus' teaching here would really think that gay sex was in any way implicated, anyway. In fact Jesus' teaching about neighbour love and love in relation to behaviour would tend to point towards allowing responsible, loving, committed homophile relationships as a just and loving way to proceed.

It seemed to me, too, that there is a fundamental problem with a reading of a moral argument in scripture that works oppressively, when the underlying deep structure of scripture is about love and justice. But that is not necessarily decisive if there is a possibility that there could be something about the practice that turned out to be ultimately injurious in terms of love and justice. But it seems to consistently emerge that the injurious things turn out time and time again to be the results of things that would be similarly injurious amongst heterosexual people, that is, they are nothing to do with homosexuality per se.

The other major text for me was -and for many evangelicals (but not fundamentalists -who tend to read so flatly that any text apparently about homosexuality is simply read across without much hermeneutical work) still is- the argument in Romans 1. But here I think the argument is strong that the characteristics listed in verses 29ff don't fit faithful committed gay Christians and therefore their situation is not in view. Similarly it seems to me that gay Christians do not fit the profile of idolatry in verse 23 and so the 'giving them up to' of verses 26 and 27 simply does not apply. Therefore it is reasonable to read this part as general condemnation of idolatry and its effects on general social morality -which may include people engaging in experimental sex outside of intentionally lifelong partnerships (and possibly, in the original context, kinky sex as part of 'religious' rites).

So, all in all, I don't think that the complementarity of the sexes is sufficient reason for continuing to define marriage exclusively in heterosexual terms. I certainly don't think that it would be a reason to put at peril the church's position as a legal registrar of marriages. Even for those who don't think as I now do on the topic: I can't see it's much different from the issue of marrying divorcees in church -a matter of conscience can be accommodated in such a case -and given that it is now easier to be married in parishes one is not domiciled in, the possibilities of finding clergy who can in conscience preside over the ceremony.

I'd commend following this up by having a look at this web-site. Also read this sermon.

Note that some minor revisions of wording and addition of headings took place a few days after posting this article.

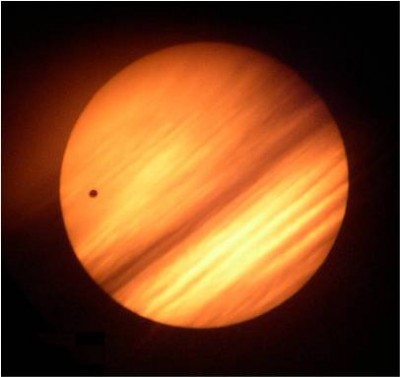

GeoevoBible

I kind of like this image. I think that it may kind of say that the Bible is in the geological record, and that kind of validates the idea that creation and evolution aren't rival stories but complementary stories. Or am I missing something with this image?

It kind of reminds me of one of the radio episodes of Hitchikers' Guide to the Galaxy where Arthur Dent sees a layer of rubber in the geological strata on one planet and is told the story of a culture that overdosed on shoes ...

13 June 2012

Prometheus, the universe and life

I went to see the film last week with one of my sons. We came out with a lot of questions and not necessarily in a good way.

Prometheus: what was that about? Ten key questions | Film | guardian.co.uk . But then there's one I asked that's not on their list. In fact it's the same basic question I asked of at least one of the Alien films and also regularly ask about other sci-fi and/or horror films. it's a bio-ecological question. In the case of Prometheus it comes into sharpest focus with the alien beastie that comes out of Elizabeth's womb in the emergency c-section/abortion. That beastie is about the size of a human neo-nate in terms of mass (why Elizabeth didn't 'show' more is another good question btw). When we next see said beastie it has become I would say four to eight times the womb-leaving size. ... How? Leaving aside the rate of growth which I'm willing to suspend my disbelief over- where has the critter found the protein and other compounds it would need to have ingested to convert into that kind of body mass. The room it was trapped in was sterile and had no significant amount of biological material to convert into more of said beastie's body. This issue is also part of at least one other of the the Alien films.

A related issue is the sheer amount of alien carcasses in what turns out to be the Engineers' ship: again; what have the beasties fed on to become so big? While some Engineers clearly were colonised, we seem to be talking about an aggregated mass of alien body-stuff many times that of the captured Engineers' body-stuff. There are well-known ratios of predators to prey in established sizes of ecosystems; the Aliens seem to have the secret of making body-stuff out of thin air. In which case, why bother feeding off other living beings?

I prefer my sci-fi to have greater plausibility in the face of such questions.

PS: I've just (3 July) found a review of the film that actually gives it a lot more sense symbolically but also helps some of the plot plausibility by reckoning that the black goo is an adaptable stuff that is shaped by the emotional atmosphere of those around it -in this case the greedy and rapacious homo sapiens around it produce their own nemesis; but had 'they/we' been more gentle or convivial, the goo would have shaped into a life form of friendlier and more helpful disposition. I'm expecting, on this basis, for the next film to be called Nemesis!

A voyage into the unknown that conjures more questions than it answers … That's what we were told to expect from Ridley Scott's long-awaited sort-of-Alien-prequel Prometheus, ... We thought they were talking about the characters' journey into the depths of space to meet the extraterrestrial originators of life on earth. It turned out, though, to refer to us poor lugs in the audience, stumbling out into the night scratching our heads.So I was interested to find this article which asked the same questions and then a couple more ...

Prometheus: what was that about? Ten key questions | Film | guardian.co.uk . But then there's one I asked that's not on their list. In fact it's the same basic question I asked of at least one of the Alien films and also regularly ask about other sci-fi and/or horror films. it's a bio-ecological question. In the case of Prometheus it comes into sharpest focus with the alien beastie that comes out of Elizabeth's womb in the emergency c-section/abortion. That beastie is about the size of a human neo-nate in terms of mass (why Elizabeth didn't 'show' more is another good question btw). When we next see said beastie it has become I would say four to eight times the womb-leaving size. ... How? Leaving aside the rate of growth which I'm willing to suspend my disbelief over- where has the critter found the protein and other compounds it would need to have ingested to convert into that kind of body mass. The room it was trapped in was sterile and had no significant amount of biological material to convert into more of said beastie's body. This issue is also part of at least one other of the the Alien films.

A related issue is the sheer amount of alien carcasses in what turns out to be the Engineers' ship: again; what have the beasties fed on to become so big? While some Engineers clearly were colonised, we seem to be talking about an aggregated mass of alien body-stuff many times that of the captured Engineers' body-stuff. There are well-known ratios of predators to prey in established sizes of ecosystems; the Aliens seem to have the secret of making body-stuff out of thin air. In which case, why bother feeding off other living beings?

I prefer my sci-fi to have greater plausibility in the face of such questions.

PS: I've just (3 July) found a review of the film that actually gives it a lot more sense symbolically but also helps some of the plot plausibility by reckoning that the black goo is an adaptable stuff that is shaped by the emotional atmosphere of those around it -in this case the greedy and rapacious homo sapiens around it produce their own nemesis; but had 'they/we' been more gentle or convivial, the goo would have shaped into a life form of friendlier and more helpful disposition. I'm expecting, on this basis, for the next film to be called Nemesis!

06 June 2012

Philosophy still teach science a lesson

I like this little selection of correspondance about the relationship between philosophy and science.

Letters: Philosophy can still teach science a lesson | Education | The Guardian:

The most negative comment is this:

So it was good to see one correspondent writing:

I guess I'd not put it as 'needs no help' so much as 'realises that it is inevitably immersed in philosophical issues and should learn to do them well'.

Letters: Philosophy can still teach science a lesson | Education | The Guardian:

The most negative comment is this:

Stephen Hawking was right to insist that philosophy is dead. It should be, for, as another leading scientist Steve Jones opined, "philosophy is to science as pornography is to sex"And I wasn't quite sure I understood it. It sounds like a plea for fundamentalist positivism. Though I wonder whether the quote within that quote is saying that while science actually does the stuff, philosophy just looks on and drools. That would be positivistic, I think: science done without heed to the bigger questions and to its own limits and assumptions and their implications is prone to produce people who make elementary mistakes. Stephen Hawking really ought to know better: the elementary mistake of not paying attention to what 'nothing' might mean, for example might have avoided a rather embarrassing gaffe ...

So it was good to see one correspondent writing:

given the messes that popular and some other science has made of the subjects of time, the mind, the nature of religious utterance, and consciousness above all, it is ignorant to suppose that that science needs no help.I think there's a pot-shot at the challenged pronouncements of certain new-atheists, rightly.

I guess I'd not put it as 'needs no help' so much as 'realises that it is inevitably immersed in philosophical issues and should learn to do them well'.

Two faced by the sun

I've been avoiding the sun for about 15 years now: fair skin and a tendency to burn easily plus celtic ancestry make me a prime candidate for some kind of -noma. So it's with a sense of 'Boy I'm glad I'm doing this' that I view this picture

Check out the backstory -but that's not a made-up face; it's a real person. One face, but two sides of a story | Society | The Guardian:

Check out the backstory -but that's not a made-up face; it's a real person. One face, but two sides of a story | Society | The Guardian:

The left-hand side of the 66-year-old's face is deeply lined, pitted and sagging after 28 years of sun exposure through the side window of his lorry. The right-hand side, shaded by the cab as McElligott delivered milk around Chicago, is the taut, unblemished face of an apparently much younger man.And apparently people who drive with their hands in the sun should also be wary ...

05 June 2012

I am a strange loop

I've just finished reading Douglas Hofstadter's book I am a Strange Loop. It's been a lot of fun: he seems to share my love of puns and wordplay and his little illustrative stories and scenarios are replete with them. I commend the book if you are looking for a well-explained (some who are more familiar with the ideas might just find it laborious at times) primer for the intelligent general reader that explores how human consciousness might just be an emergent property of human brains and not a non-physial dualistic sort of thing. It's very suggestive too, the picture that emerges (!) and I tend to think it persuasive.

What he does well, I think is to help the reader to make a transition from our instinctive dualism (which is driven by our perceptual and hermeneutical groundedness) to seeing how a holistic view holds together and makes sense of our experience and of the things that we are beginning to know from science.

It stops short, naturally, of thinking about the implications as picked up by the likes of John Polkinghorne for an account of human existence beyond biological death, but it lays a good foundation for understanding why Polkinghorne would want to reframe the Christian account as he does. That is to say; in non-dualistic terms consonant with what we know about how material reality is structured.

The eponymous strange loop is a usage of Godel's discovery which unpicked Whitehead and Russel's great work Principia Mathematica and came up with the incompleteness theorem (along the way making the maths somewhat clearer to this non-mathematician) and showing that the awkward and untidy self-referentiality they had tried to remove from logical principles was never going to go away. Hofstadter then goes on to show that the self-referential structures are in the maths because they are in the world and he postulates and evidences the idea that they are the basis for emergence and in particular the emergence of consciousness.

I don't think that there is anything here to worry a Christian reader -unless that Christian was wedded to a particular kind of stance in which dualism is non-negotiable and the results of scientific endeavour were regarded with disfavour or fear. I would of course argue that such a stance is not consistent with some important strands of biblically-informed thinking ...

For me the interest is that the account of human consciousness emerging, gives a glimmer of a possible mechanism for the emergence of corporisations which was a major reason for me looking at the book in the first place.

What he does well, I think is to help the reader to make a transition from our instinctive dualism (which is driven by our perceptual and hermeneutical groundedness) to seeing how a holistic view holds together and makes sense of our experience and of the things that we are beginning to know from science.

It stops short, naturally, of thinking about the implications as picked up by the likes of John Polkinghorne for an account of human existence beyond biological death, but it lays a good foundation for understanding why Polkinghorne would want to reframe the Christian account as he does. That is to say; in non-dualistic terms consonant with what we know about how material reality is structured.

The eponymous strange loop is a usage of Godel's discovery which unpicked Whitehead and Russel's great work Principia Mathematica and came up with the incompleteness theorem (along the way making the maths somewhat clearer to this non-mathematician) and showing that the awkward and untidy self-referentiality they had tried to remove from logical principles was never going to go away. Hofstadter then goes on to show that the self-referential structures are in the maths because they are in the world and he postulates and evidences the idea that they are the basis for emergence and in particular the emergence of consciousness.

I don't think that there is anything here to worry a Christian reader -unless that Christian was wedded to a particular kind of stance in which dualism is non-negotiable and the results of scientific endeavour were regarded with disfavour or fear. I would of course argue that such a stance is not consistent with some important strands of biblically-informed thinking ...

For me the interest is that the account of human consciousness emerging, gives a glimmer of a possible mechanism for the emergence of corporisations which was a major reason for me looking at the book in the first place.

Monarchoskeptical thoughts on a jubilee

I used to think that the response illustrated was a bit OTT. But attention-getting.

More regular visitors here may have picked up that I'm no royalist. My reading of scripture feeds my natural skepticism about accumulation of power in human hands. So you can imagine I'm a less than whole-hearted celebrant of this jubilee weekend in GB (which I'm now avoiding calling 'UK' for the same reason). Sometimes when people discover my monarchophobia, I get asked ...

... "So, if we had a republic, who would you vote for as president, Tony Blair?",When I was first asked it, I was a bit gobstruck: why would we want to do that? Frankly I'm concerned that such an interlocutor thinks (a) that Blair might stand and (b) most people would vote for him. However, that's not a snappy answer. So there are some good ripostes, I thought, in some recent Guardian correspondence.

answer, "No, the Queen, she'd be rather good at it." They never know what to say.

I think that that's definitely a good 'wind out of the sails' riposte. on the same lines and even better put:

If, when the Queen dies, British people were offered the chance to vote between the option of King Charles, with the continuation of the royal succession, or President William Windsor as the first elected head of state, how would they vote?Which is very like one of my scenarios for a transitional arrangement: first an elected monarch, then opening the candidature to a wider field... just a thought. Anyway, the sneer card also gets played in the correspondence:

..The way I look at it, I'd prefer a titular head who belongs to a bunch of benign, horsey, fancy-dress freaks (who bring in a few quid from tourists) to a President Blair, Cameron or (God help us) Johnson.This seems to me to be actually rather unpleasant as politics: it suggests a contempt for the electoral choices of the people and that suggests a hidden contempt for democracy. Admittedly democracy is merely the least bad system of government (Winston Churchill's bon mot, I believe). What is actually being said here is that the British people can't be trusted to elect a head of state that the correspondent approves of. That's just thinly disguised elitism; the next step is to tell us some people are genetically more capable of governing ... It might be fair to let them have candidates from family lines that have traditionally made or accepted that claim on their own behalf: if they can persuade enough of the electorate ... but I would bet that no-one made that their election manifesto: "vote for me: I'm born to rule".

I found the most interesting comment in an article by Andrew Rawnsley, here:

The oddity of monarchy is that it is an institution embodied in a personality. In a democracy, it survives only by popular consent and that depends on the character of the incumbent. If republicans want a straw of comfort, then it might be found in polling that indicates that only 39% of the public want the crown to pass on to Prince Charles, more preferring it to go to Prince William – which demonstrates that most Britons either have an infirm grasp of the principles of hereditary monarchy or not much respect for them. The Queen may pass on the throne to her heirs and successors. What they can't inherit is her personal popularity.That puts the matter quite nicely, I think: the irony that even monarchists in our not-quite-yet republic don't really believe in the hereditary principle -and therefore not monarchy. Rather, they believe in a person who has managed to ride the waves of celebrity very cannily.

But there may be one further thing to be explored. As a Church of England clergybeing I can only hold office if I make a declaration which says, inter alia,

... I will be faithful and bear true allegiance to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth, her heirs and successors, according to law. So help me God.'.I think that 'faithful' and 'true allegiance' means that I I will support her government in a way that is appropriate in a parliamentary democracy (that is her form of government, after all; I don't think we're being asked to prefer a less 'constitutional' arrangement) which means that there is room to exercise loyal opposition. That includes proposing and arguing the opinion that the government would be best if it were a republic. It means that I do not propose to further that opinion by any illegal means and in the meantime (before 'my' preferred constitutional arrangements are in place) I will support HM and her government by loyal constitutional subject-hood (which I would like to convert into republican citizenship). Heirs and successors? Yes -'according to law' -I hope that we might secure a change of the law so that hereditary succession to the head of state position would be replaced by a more democratic method. I do not advocate overthrow, merely an orderly and legal change to the principle of succession. I do so out of no animus against the persons of the monarch and likely successors under the hereditary principle. I simply do not believe that it is right and good for them to be in that position or for us to continue to allow it (and some of my reasons show up in this article where two biblical trajectories are mentioned one of which -I think the predominent one- is monarchoskeptical). It is not good and right that we put people in the positon they hold. The present Queen has done about the best anyone could do with the situation. We cannot guarantee that any of her progeny will do so and we should not, out of pity, ask them to.

I do not believe that the declaration (some take it as an oath) is meant to force one to be an ardent monarchist --unlike, arguably, the precursor version which starts "I, A. B., do utterly testify and declare in my conscience that the Queen's Highness is the only supreme governor ..." which seems to require more conviction, though in recognising a fact is capable of allowing one to support a change, I suspect; it's real target, of course, was those who in conscience thought that the Pope had the trump card in supreme governorship. The amendment allows RC's to take up office, and with it allows greater lassitude for others to imagine and to propose alternative constitutional arrangements.

So all in all, I think I'm sanguine about this: "MPs back proposal to change name of east tower at the Palace of Westminster despite republican protestations"

I realise that I'm not a hardline republican when I see that. I can't really see the harm in it. Especially as I note that they are proposing to call it the Elizabeth Tower rather than the Queen Elizabeth Tower: I think the implicitly republican naming is a bit of fun really! The objection has been "Republic has criticised the proposal as "crass and profoundly inappropriate given that the tower in question is a landmark of our democratic parliament"." -but then see me previous remark. That said, I think the group in question, in general, should be heard, so if you've read this far, have a look.

04 June 2012

Warm fuzzy blessing and missional purpose

My one-time fellow ordinand, Doug Chaplin, has many good things to say and I'm glad subscriber to his blog, not least because he continues to have this knack of telling the truth even if it's uncomfortable (whether he'd recognise this, I don't know; we are probably aware -most of us- of how our inner and less-viewed lives may not always live up to our more carefully lived socially-viewed living). And recently he wrote a provoking but important-to-question post on a common amendment some clergy make in the blessing at the end of services. Here's the post: Blessings and warm fuzzies and here's the guts of the issue:

I think he's right and I have tended to resist it myself because I've similarly felt that it is too 'cosy' and implicitly feeds the worst excesses of family-friendly ministry in excluding from view the hard cases. Of course it could be argued that those whom we love should precisely be those who are enemies or persecutors -but actually, we all know, that's not going to be the primary understanding unless we are taught it carefully. No, Doug is right; this addendum 'works' because the primary reference will be taken to be our family and perhaps some family-like friends (usually the courtesy aunts and uncles to any children we have).

Partly in response for a number of years, I sometimes fill out the blessing myself. However, I have tried to keep a connection with a missional intention, as both Doug and I understand it (I think). I may sometimes say "... and with those whose lives your lives touch." In doing so I'm trying to keep the wider view of neighbour love beyond the immediate circle and also convey the idea that we are blessed in order (at least in part) to carry/be blessing to others.

Not sure that Doug would approve, but it was helpful to see someone else articulate the disquiet I have long felt about the form I reacted against to produce my own addendum.

... that form of blessing where clergy intone “the blessing of God almighty, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, be with you and remain with you and those whom you love, now and always. Amen.”He questions this on the basis that

“Those whom we love” ... But the point of the dismissal is to send us into a world in which we are called to treat anyone in need as a neighbour to love, bless those who persecute us, and love our enemies. Including a cosy reference to families and friends to make people feel that the vicar really cares about them works badly against that intention.

I think he's right and I have tended to resist it myself because I've similarly felt that it is too 'cosy' and implicitly feeds the worst excesses of family-friendly ministry in excluding from view the hard cases. Of course it could be argued that those whom we love should precisely be those who are enemies or persecutors -but actually, we all know, that's not going to be the primary understanding unless we are taught it carefully. No, Doug is right; this addendum 'works' because the primary reference will be taken to be our family and perhaps some family-like friends (usually the courtesy aunts and uncles to any children we have).

Partly in response for a number of years, I sometimes fill out the blessing myself. However, I have tried to keep a connection with a missional intention, as both Doug and I understand it (I think). I may sometimes say "... and with those whose lives your lives touch." In doing so I'm trying to keep the wider view of neighbour love beyond the immediate circle and also convey the idea that we are blessed in order (at least in part) to carry/be blessing to others.

Not sure that Doug would approve, but it was helpful to see someone else articulate the disquiet I have long felt about the form I reacted against to produce my own addendum.

02 June 2012

Mutiny! – Controlling the means of Production

Kester Brewin has been blogging a lot about piracy (mostly as a kind of way of asking questions about economics and power and culture). It's very interesting, then, to see that he's going to publish in the parate spirit. That is, he's going to self-publish in DRM-free e-format and offer a ppb as an option or a hand-crafted hardback. Nice.

Kester Brewin Mutiny! [1] – Controlling the means of Production:

Mutiny! is going to be self-published, and that’s a step that I’ve taken deliberately. I’ve spoken to publishers too, but I’ve decided to go down this route, and I’m really excited about it

I am too. I think that if you're not mass market novelist, there is decreasing reason to go via normal publishing routes; publishers no longer can be relied on to connect writer with audience and to make the best financial deal for the author. Disintermediation makes sense unless you don't want to bother with chunks of the process and are happy for someone to take a big chunk of the profits. About the only thing that this seems to make sense for is the marketting. But then, look at how many books get remaindered despite get a marketting deal as good as many of those that sell. Being picked up by a publisher is no guarantee of sales. So with the outlay on an e-book being so small, what do you need publishers for? Say you made 90p on each sale of your paperback being sold at six quid. Well, you could sell your ebook directly for 4 quid and make most of that back. Offer a print-on-demand option for those who prefer a paper book and you're still doing well. The real trick is to be able to get connected with your potential audience. And for many people writing more 'niche' books, you probably already have that. So good on you Kester.

Kester Brewin Mutiny! [1] – Controlling the means of Production:

Mutiny! is going to be self-published, and that’s a step that I’ve taken deliberately. I’ve spoken to publishers too, but I’ve decided to go down this route, and I’m really excited about it

I am too. I think that if you're not mass market novelist, there is decreasing reason to go via normal publishing routes; publishers no longer can be relied on to connect writer with audience and to make the best financial deal for the author. Disintermediation makes sense unless you don't want to bother with chunks of the process and are happy for someone to take a big chunk of the profits. About the only thing that this seems to make sense for is the marketting. But then, look at how many books get remaindered despite get a marketting deal as good as many of those that sell. Being picked up by a publisher is no guarantee of sales. So with the outlay on an e-book being so small, what do you need publishers for? Say you made 90p on each sale of your paperback being sold at six quid. Well, you could sell your ebook directly for 4 quid and make most of that back. Offer a print-on-demand option for those who prefer a paper book and you're still doing well. The real trick is to be able to get connected with your potential audience. And for many people writing more 'niche' books, you probably already have that. So good on you Kester.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Retelling atonement forgiveness centred (10)

After quite a while, I return to this consideration because Richard Beck wrote a very interesting blog post about forgiveness. It's prov...

-

I'm not sure people have believed me when I've said that there have been discovered uncaffeinated coffee beans. Well, here's one...

-

"'Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets; I have come not to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I tell yo...

-

Unexpected (and sorry, it's from Friday -but I was a bit busy the end of last week), but I'm really pleased for the city which I sti...